I found an article on a site called the Mining History Association, written in 1999, that does a really good job of painting a picture of the atmosphere and the complexity of the political and labor conditions in Bisbee in 1917. As the author, James McBride, described the climate of tension and fear leading up to the strike, I kept imagining my great-grandparents in the midst of it, with baby Ivy.

I feel a little bad about diluting this story, and possibly glossing over important or interesting details, but I want to convey the gist of it, without simply rewriting the article. (This is the article in PDF format.) Here goes.

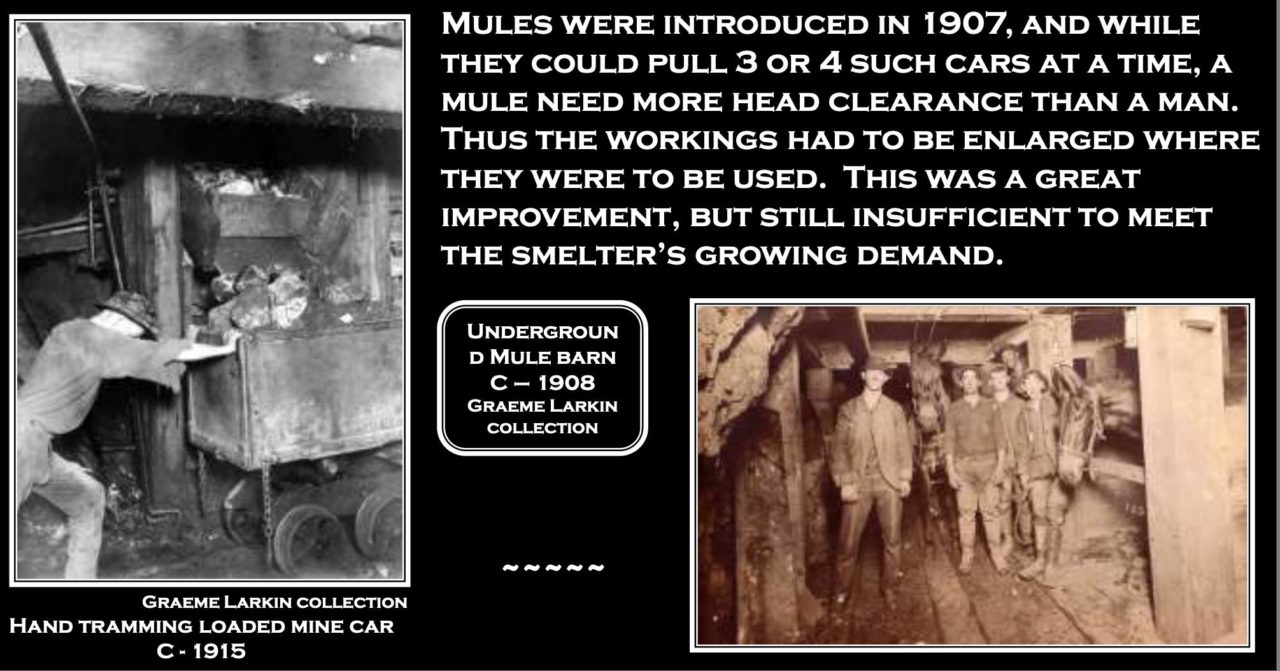

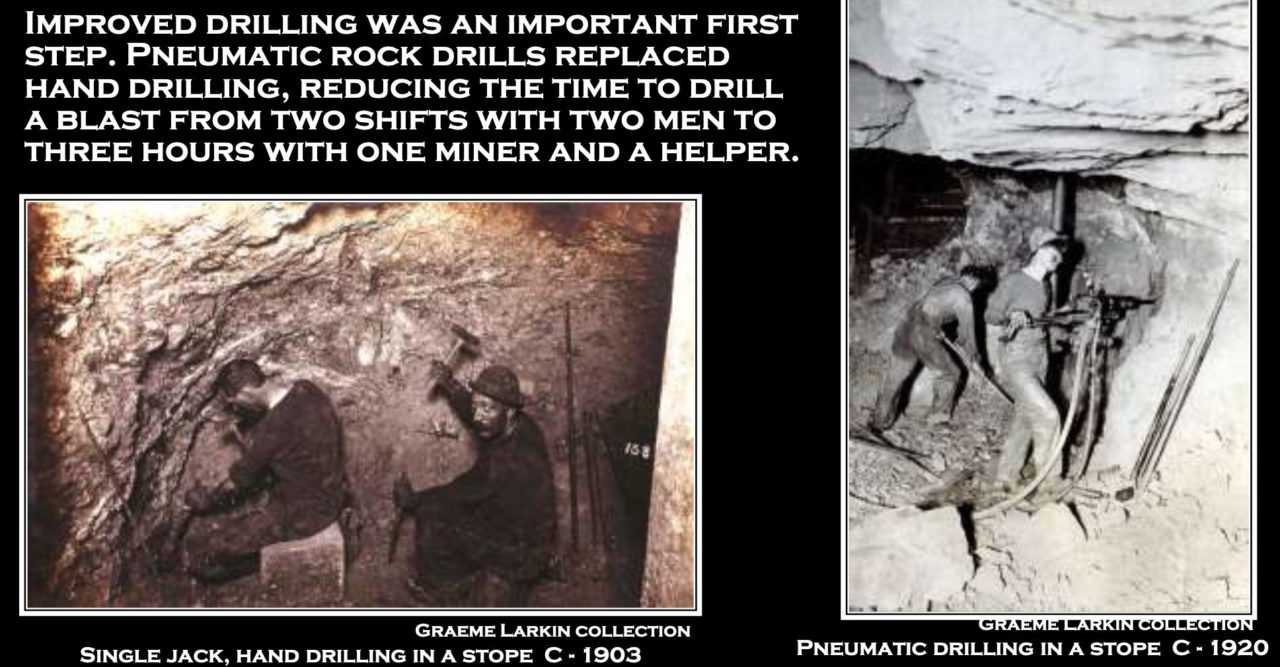

The Industrial Revolution had arrived in Bisbee, with the tensions between the paternalistic owners of the means of production and the workers who were expected to work more, produce more, faster, and more efficiently. Under particular pressure to produce for the war effort, the arrival of union organizers was not entirely unwelcome to the miners. Apparently, Bisbee was unusual in that unionizing efforts, demonstrations, and meetings were not generally violent. The mining companies did not overreact and the miners were careful to behave in a lawful and orderly way.

But the union organizers did not go away, either. And when the mine owners were making so much profit, and production was ramping up, more men were open to the idea of going to the owners with some demands. After a few failed attempts at smaller scale strikes, these demands were presented in June, 1917:

- The abolition of the physical examination

- Two men to work all machines

- Two men to work on all raises

- To discontinue all blasting during shifts

- The abolition of all bonus and contract work

- To abolish the sliding scale. All men underground a minimum flat rate of $6 .00 per shift. Top men $5.50 per shift.

- No discrimination to be shown against members of any organization

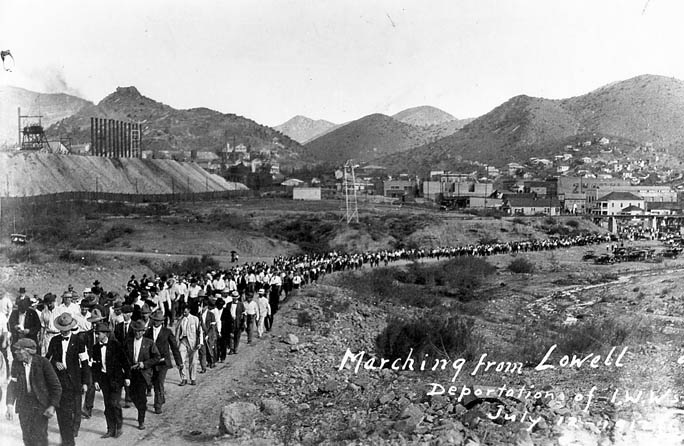

Tension escalated and the owners decided they needed to purge Bisbee of anyone who would join the strikers. In the early morning of July 12, 1917, newsboys ran through the streets warning that women and children should stay off the streets. Then armed men went door to door, pulled men out of their beds, asked them if they were working (weird, since if they were in bed, they were clearly not at the mine, working) and then took them to be detained at the city post office, in the center of Bisbee. (They never asked for proof of membership in a union, which became the basis of the men’s lawsuits over the next several years, because there were men who were not union supporters who were detained.)

By the end of the day, there were over 1,000 men detained. They were marched out of Bisbee and then shipped by train to Los Hermanas, New Mexico. They were told to get off the train and not ever return to Bisbee. The US government, Woodrow Wilson specifically, thought this deportation event looked bad so they sent supplies, food, and tents for the men, who were essentially stranded and far away from their homes and families. They built a makeshift refugee camp and that is where the men spent weeks and months, depending on their individual circumstances.

This is a picture from archive.net, of the crowds of men, marching out of Bisbee.

AHS, Pictures-Places-Bisbee-Bisbee Deportation, #43174.

Also on a postcard at UA Special Collections, Bisbee-Bisbee Deportation.

Of the demographic composition of these 1,000 men, McBride writes, “80 percent of those deported were immigrants, 33 percent of those being Mexican, 28 percent Slovaks, 12 percent Russian, and Finns, and 27 percent a mix of other Europeans. In terms of union affiliation the deportees were evenly divided: 33 percent of those deported were Wobblies, 33 percent were American Federation of Labor (AFL) members and 33 percent were non union.”

“Wobblies” was the nickname for the members/supporters of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). The Wobblies were known for their stance against World War I; the IWW had a more leftist, socialist bent to their ideology. As much as the miners may have been drawn to the benefits which unionizing promised, many of them were also recent immigrants from countries under attack from Germany. They were not uniformly against the US joining the war because they wanted to defend their home countries.

In addition, half the men were US citizens! Some of them were naturalized citizens and some were US-born. Not to suggest that US citizens could not be pro-union, but being a citizen did not provide cover, either. This was not simply a purge of the “foreign element.”

All of which is to say, this was a complex, frightening, uncertain situation for everyone. The fact that now I can more easily picture Nelson and Jean in this situation makes it an even more compelling story to me. The image of men pulled out of their beds and marched out of town is eerily reminiscent of other times in history and it sort of gave me the chills, when I read it. How did Nelson avoid it? Surely Nelson and Jean knew families who were effected by this upheaval. The whole town would have been effected, I think. What would losing 1,000 workers do to the mine’s output? It just seems like a disaster, in every way.

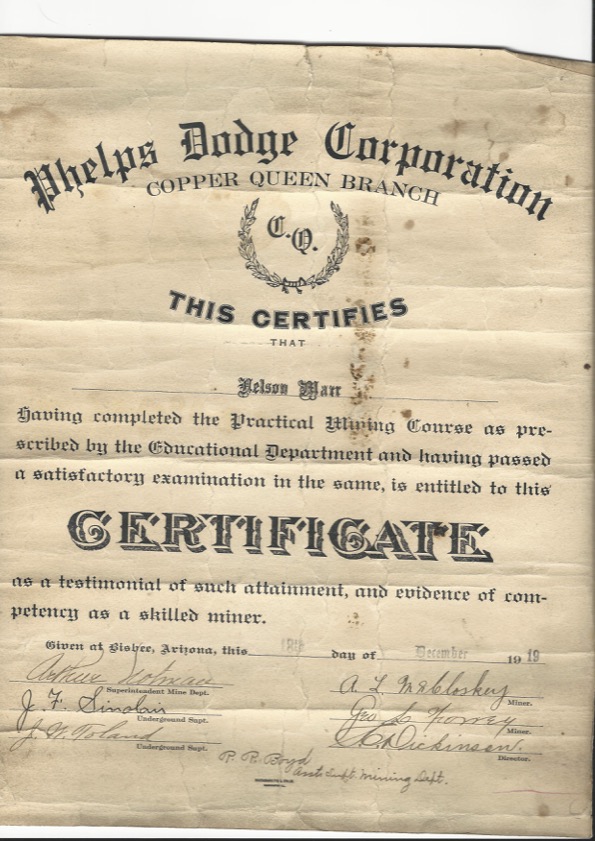

I don’t have any pictures of Nelson in a mine. I have the certificate he received authorizing him to work as a miner. When I looked at it a few weeks ago, at my parents’ house in Georgia, I thought, Well, that’s interesting but I am not sure what significance I should ascribe to it. Now, I have context to understand its significance to Nelson’s ability to take care of his family, which by 1919 included my grandmother, Jeanne.

It is dated December, 1919. Nelson had been in Bisbee, working as a miner (I thought) since 1914. His Petition for Naturalization is dated July, 1919. I don’t know what to make of this, but now that I know the certificate was issued after the deportation of 1917, it seems like there is a story here. A story I may never know anymore about.

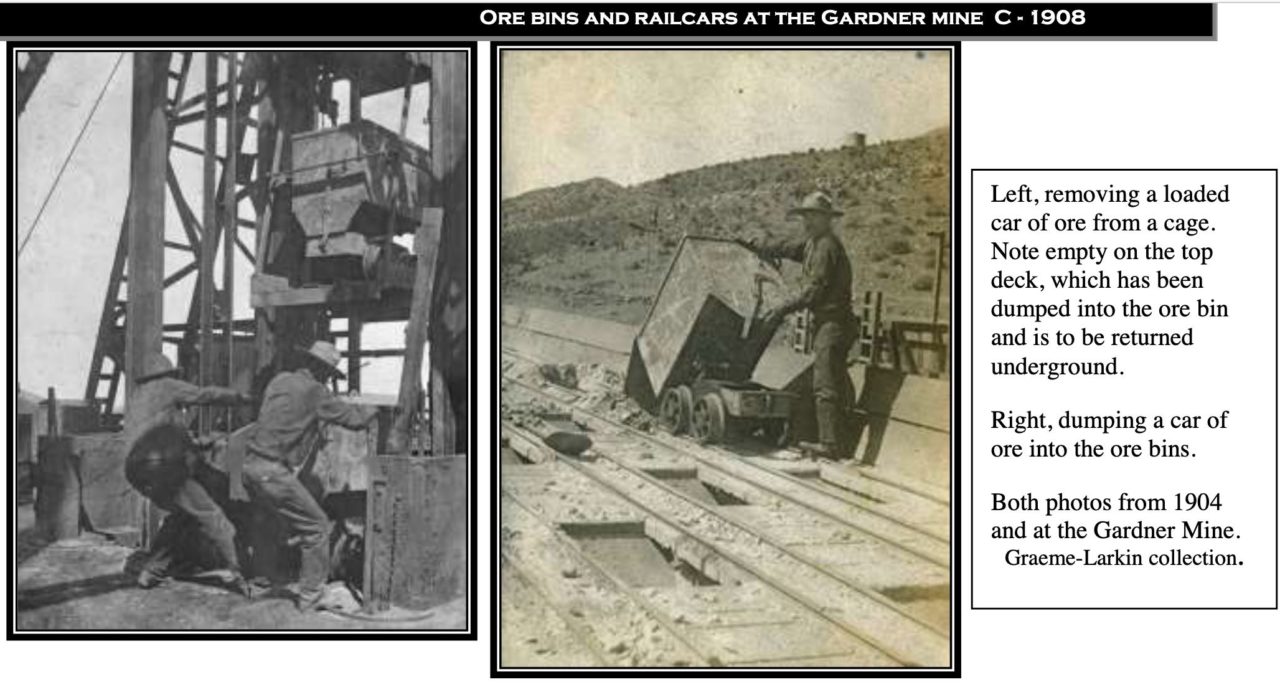

Did Nelson try to just keep his head down and stay quiet? To keep his job and get his citizenship, so he and Jean would feel safe to stay? I found pictures from the Bisbee mines on another site called Bisbee Mining and Minerals, which give some sense of the work he – and his brother, John Thomas – must have been doing.

I don’t remember my grandmother telling me stories about Bisbee. I only remember her saying she was born there, but had no memories of it herself. What I do know is that my great-grandfather worked for the city of Santa Monica, in the police department, for over 30 years. At the risk of over-reaching, I wonder if that job allowed for both a sense of security and the benefits of belonging to a union, neither of which he would have had in Bisbee, Arizona.